In 1860, the institution of slavery was as healthy as ever. Cotton from the South was bought at a good price, especially by the British. The cotton gin was working its miracles. For $800, one could buy a young male slave, and with him, a lifetime of hard labor. This wouldn’t pay a free white laborer’s wages for 3 years. Slavery, despite its abhorrent moral wrongs, made economic sense. How then, did it manage to die far before its economic value eroded?

The answer is simple: people made it stop. While the immediate abolition of slavery where it existed was not an initial Union war goal, the Southerners were correct that Lincoln would eventually tamper with it. In 1857, the slavery expansionists struck a major blow in the Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sanford. Slavery was deemed a status under federal law; residence in a free state would not grant free status. The Dred Scott case made the legal designation of a “free state” nearly meaningless, and paved the way for slavery from sea to shackled sea. Expansion of slavery to the west would have outflanked the abolitionists and those who wished to contain slavery. Slavery would have integrated itself into our society, laws, and economy beyond hope of removal. Lincoln, and the Republican party were firmly opposed to this expansion, and were supported overwhelmingly by the North. The Civil War was about state’s rights: the North asserted its right to be free of slavery by electing Lincoln, and the South responded with war.

Eventually, the realpolitik of Lincoln, the convictions of James Mitchell Ashley, and the military genius of General W.T. Sherman, American chattel slavery was ended. Political and moral forces united to defeat a strong economic force. None of the parties involved were socialists, communists, or in any way ideologically opposed to the free market; the following period was marked by its Laissez-faire economics with the notable lack of slavery.

But what does this have to do with 21st century computers?

Tech boffin Elon Musk fears that a nation with AI running its defenses may instigate a nuclear war. That is possible, but another, more mundane threat has also been long feared, and for good reason. What good will we meatbags be in the world worked, designed, and ruled by superior beings of silicon and copper? The days when the world was forged by human muscle and sweat ended with John Henry. Advancements since then have generally affected desirable change, freeing the mind from the body, increasing productivity and standards of living. This loop of human use is closing. Our minds will be bottlenecks to machine-led progress, and we’ll be of no use in developing the next generation of machines.

All of these positions have been stated, refuted, and advocated by much more qualified individuals. The one issue affecting all three of them is the assumption that the growth of knowledge will always be closely followed by the growth in use of the new technology.

While automation lacks the human suffering and immorality of slavery, it fills a similar economic role. It provides the ability to get work done quicker and more efficiently at a low upfront cost. The arguments for them are similar: they are objectively superior at the margins, and whoever doesn’t use them will fall behind. Indeed, the South never regained its position in the world of cotton. British colonies in Egypt filled the position left by the blockaded south, and never returned it. Slavery nevertheless ended, because people fought and struggled to make it end. These supposedly unstoppable economic forces that claim control of human destiny were defeated by human conviction and courage.

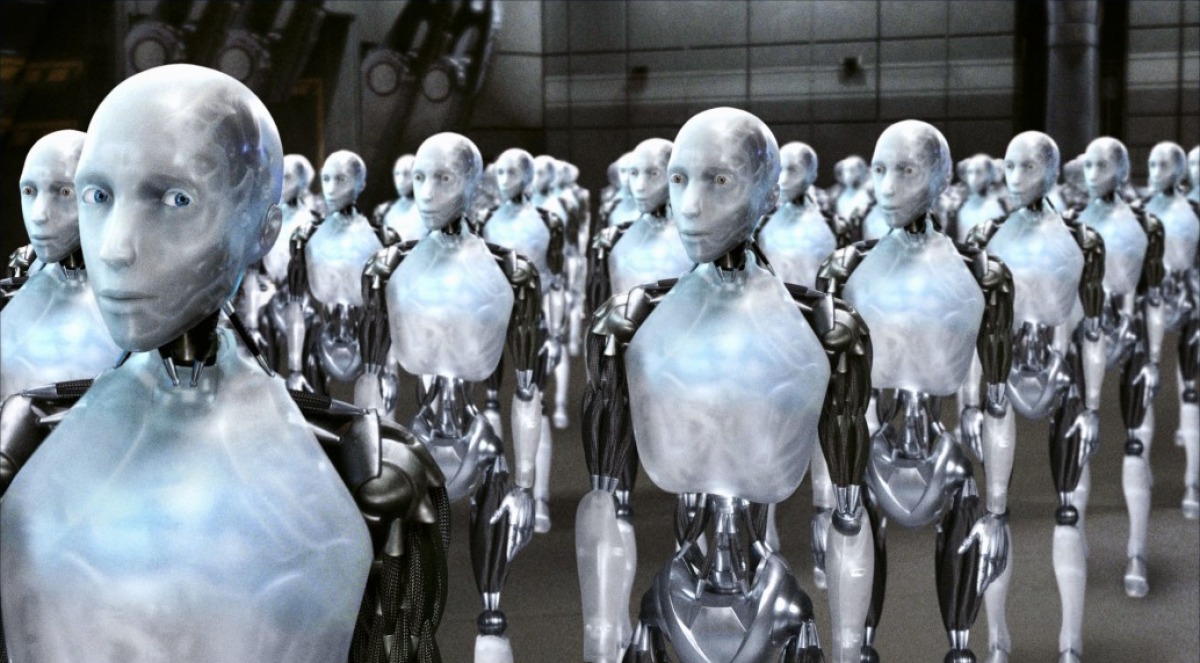

American culture has long been interested in this issue, but in a typically Hollywood, asinine way. The Terminator, The Matrix, and other ripoffs of Frankenstein, all have the same theme: arrogant humans. Insert a trite “moral” at the end and a hunky actor or three and you’ve got yourself hundreds of millions of dollars worth of tech fearmongering. Not that there is anything wrong with this concept: man vs. machine was mostly novel when Mary Shelley wrote all of those stories in 1818 (with far less Hollywood rubbish).

Asimov wrote the next story about AI. His stories portray a densely populated, human-only earth co-existing, competing, and struggling against robot worked planets. This struggle doesn’t involve dodging eye-mounted lasers, but with a society of labor’s dealings with a society of leisure. This leisure ultimately ends in decline. This is the situation that we will more likely face, and whose details we need to consider.

There are many proposals on how humans can outlive their utility. One of them, a modern version of Marxism, would have these machines collectivized, owned by all the people (not the workers: those would no longer exist). All would somehow benefit equally. Another would be to greatly expand welfare, and provide a basic income for everybody; a stipend provided by the machine owners. A similar thing has been done in some Native American villages and Alaska. Champions of the free market would argue that no intervention would be necessary: if people were entirely dispossessed by loss of utility, there would be no market for the machine-owners to sell to. All of these positions have been stated, refuted, and advocated by much more qualified individuals. The one issue affecting all three of them is the assumption that the growth of knowledge will always be closely followed by the growth in use of the new technology.

The implementation of technologies that replace all human utility is dictated by nobody; it will be inevitable only if we despair at the smoke and mirrors campaign of the reigning technocrats.

This “law”, while often the case, has been broken with impunity. The advent of the nuclear bomb, for instance, seemed to many to usher in a new era of war. Wars would be decided quickly by nuclear bombing. In the darkest hour of the Korean war coincided with the the last year of absolute American nuclear hegemony. In that crisis General MacArthur, famous for his astoundingly quick loss at Bataan, protecting the Japanese emperor from war crimes charges, and for his preternatural skill as self promotion, almost brought this to pass. Communist forces held nearly the whole peninsula and its skies. We had exactly one powerful advantage: the nuclear bomb. There was no mutually assured destruction: it would take years for the USSR to develop a nuclear arsenal, and China’s program was in its infancy. Dropping the bomb could end the war, save American lives, and most importantly, acquiesce to the gods of technological progress, fighting the Next War rather than the last one.

But that never happened. The rest of the war consisted of a UN resurgence, followed by the Communist forces bringing the frontier where it is today. MacArthur was relieved of his command for requesting to drop 34 nuclear bombs on strategic targets in Korea and Manchuria. A nuclear weapon has never been launched in anger since Nagasaki. This is because opposing governments, with the support of their population (the pro-nuclear war caucus is relatively small), decided that the use of this fantastic technology would not be in anybody’s interests. Groups like the Islamic State can commit unchecked aggression against several nuclear armed powers without any fear of a their vast arsenals. “Mutually Assured Destruction” stems from a very simple principle: nobody wants to live in a post-nuclear world.

Today, opposition to the replacement of humans invites comparisons to Ned Ludd and Don Quixote: leaders of futile fights against change. The lie here is shown when people do away with economically sound systems, and letting incredible technology accrue dust. What is true is that while knowledge goes marching on, what we do with it is up to us. The implementation of technologies that replace all human utility is dictated by nobody; it will be inevitable only if we despair at the smoke and mirrors campaign of the reigning technocrats.