Last Monday, January 28th, U-M students braved the cold to attend a lecture on the language of political correctness as part of the University’s Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Symposium. Arthur F. Thurnau professors of English and Linguistics at the University of Michigan, Robin Queen and Anne Curzan, introduced themselves and their positions at the university.

“Language choices matter,” said Professor Curzan. “Every single one of us has a role in the choices… we can make to make a more inclusive language, and thereby community.” Curzan then outlined the three themes of the presentation: language choice, intention, and politically correct language.

To explain how language works, Queen defined the etymology of language, as well as the Lexical Access, or the human process of defining a word with similar sounding ones. She explained that many racialized words are negative due to semantic expression, or how the meanings of a word shift over time.

Queen used the word “niggardly” as an example of this process. She never spoke the word and claimed some people are upset they’re not allowed to say it anymore. Curzan jumped in and added “… people say ‘I shouldn’t have to give up this word because its etymology is different.’ My reaction is… why wouldn’t you let this word die?”

The two professors then dove into the idea of power in relation to politically correct language. “What are people really debating when they’re talking about P.C. language? Power… Who gets to decide what words mean and who gets to use them?” Curzan suggested that the reason political language is so controversial is that historically marginalized people are now calling the “linguistic shots”. According to Queen, changing the words you use won’t necessarily change people’s minds, but it could change the experience of those who hear the words. Therefore, it’s necessary to change language in order to change behavior.

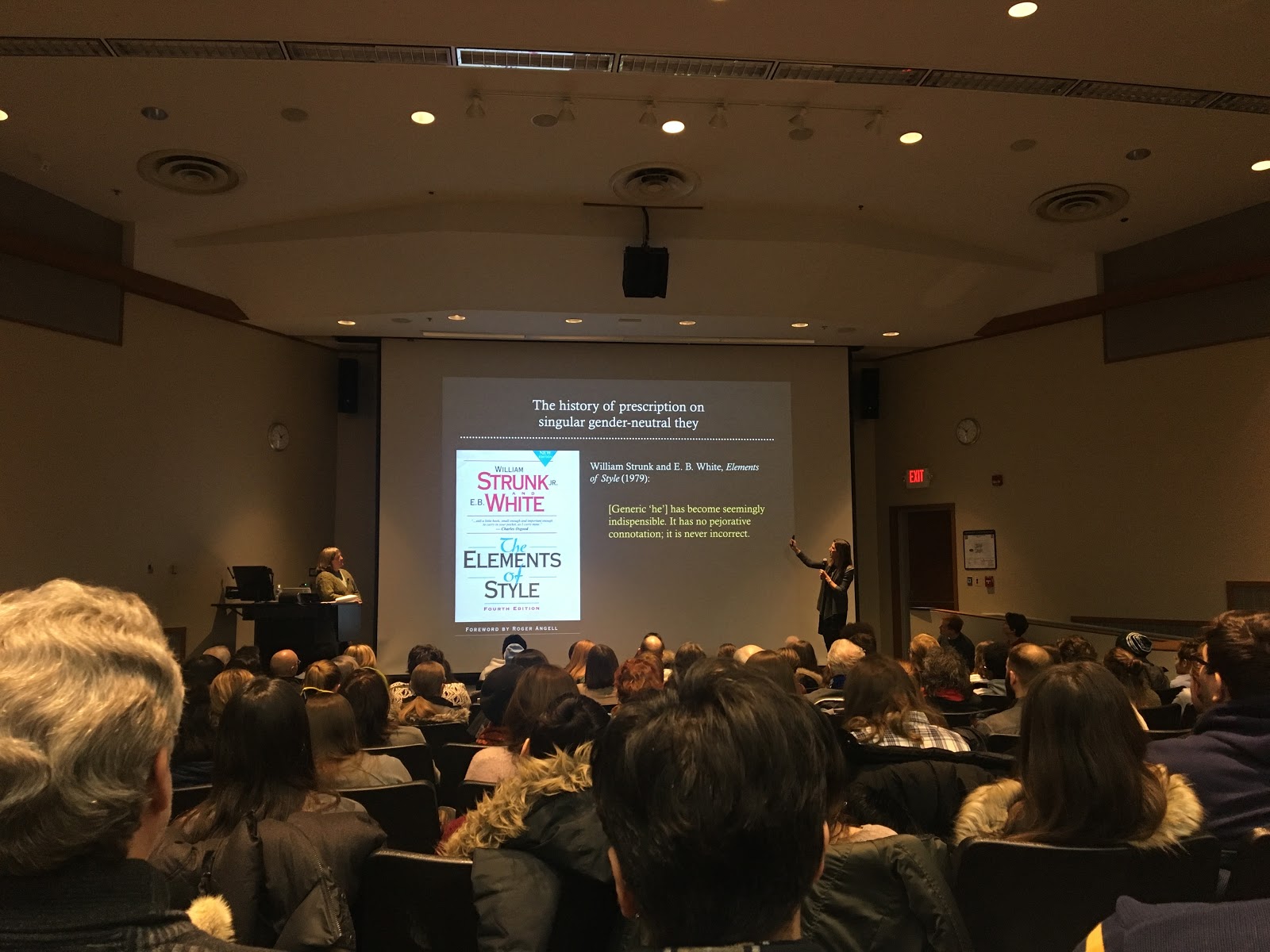

The pair also brought up the idea of public, accepted language interventions already in place. For example, the idea that public language should be civil, fair, and accurate. To them, changing language is a conscious effort that can change society and is in fact possible. Non-sexist language reform can be observed in linguistic shifts to gender-neutral words, such as “policeman” to “police officer” or “stewardess” to “flight attendant”. Similarly, the singular pronoun “they” is changing from referring to the plural “them” to a singular person. For example, choose a doctor you trust and ask for their recommendation. “What’s been leading this [momentum] is non-binary they.” Curzan and Queen then called on the audience to continue to work toward using people’s pronouns correctly.

“It’s not always up to the people in the groups to do the work to let you know, it’s up to all of us who may not know, to ask,” says Queen. When talking about intention versus interpretation, Queen stated: “It’s not up to us to determine what we mean.”

The topic of this lecture, issue in language, intrigued me. As an English major, I was interested in the linguistic aspect of political correctness. I wanted to learn how to speak “correctly” about sensitive issues. But instead, I was preached at about the importance of inclusivity in language. Curzan and Queen approached many important questions related to the language of political correctness, but failed to answer them in any concrete way. I was disappointed in the broad, unspecific presentation of P.C. language. To me, it weakened the legitimate argument for more inclusive speech, and lowered it to the tired trope of “non-marginalized people can’t have an opinion.” I walked away feeling reprimanded and with no real sense of how to change my language to be more accepting.