Many seniors are graduating this fall or next winter. It is a good time to be retrospective and evaluate whether they have a fruitful undergraduate study. A question one could ask is: is my undergraduate degree a good investment?

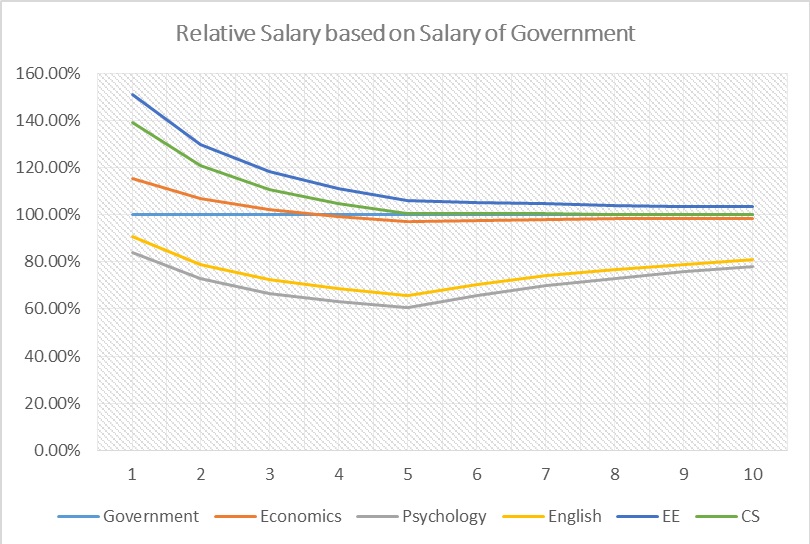

One way to answer this question is to look at the employment data as a reflection of market evaluation. According to a report by PayScale on College Salary, both the starting salary and mid-career salary are showing that undergraduate degrees in liberal art are correlated with relatively less salaries, compared to undergraduate degrees in engineering, actuarial math or statistics. Two liberal arts degrees that have the best employment data are Government and Economics. The starting salary is $42,000 for Government and $48,500 for Economics, and the mid-career salary is $95,600 for Government majors and $94,900 for Economics majors. However even those two degrees are unsatisfactory compared to Electrical Engineering (starting salary of $63,400 and mid-career salary of $106,000) and Computer Science ($58,400 and $100,000) not to mention Petroleum Engineering ($98,000 and $163,000).

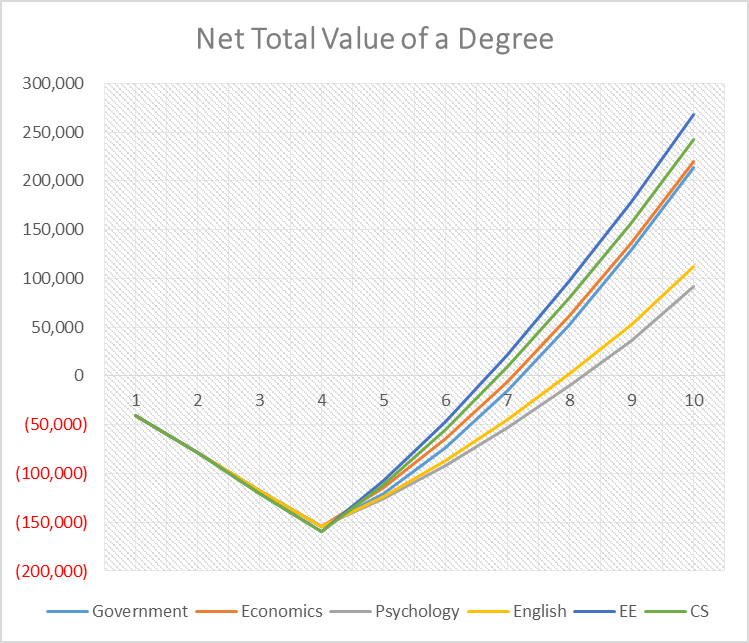

Let’s take University of Michigan as an example to factor in the costs. Let’s assume a student enters U of M and study for four years (4 fall term plus 4 winter terms), enters job market immediately after graduation, gets same salary increase every year, reaches mid-career salary after 3 years, and continues to get salary increase at the same rate. We further assume the discount rate is 5% and apply a discounted cash flow analysis to six different majors: two best paid liberal art majors, Government and Economics, two typically paid liberal art majors, Psychology and English, and two typically paid engineering majors, Electrical Engineering (EE) and Computer Science (CS), and here are some results:

- It takes about 2.5 years (after graduation) for EECS majors to earn their full tuition back, 3 years for Government and Econ majors, and 4 years for Psychology and English majors.

- The salary gap is big at the beginning, but quickly shrinks as you stay at industry and accumulate working experience.

The analysis does make the employment situation for recent liberal arts college graduates looks a little bit better, but it is still counterintuitive. Aren’t the skills most wanted by employers, such as communications, critical thinking, and presentations, exactly the focus of training in a so-called traditional liberal arts degree? Why college graduates holding an undergraduate degree of liberal arts are earning less salaries both in the entry level, and in mid-career? What exactly made the difference between employment of a liberal arts student and his friend graduating from the department of engineering, math or statistics?

First of all, curriculum design is an important reason. Education and training in an engineering degree do a better job to prepare students for future engineering jobs. College of Engineering puts weight on projects in addition to theories. Some course projects are even sponsored by firms from industry, and thus very well recognized by other firms in the same industry. On the contrary, an essay or a term paper in a liberal arts class can hardly be a convincing experience to recruiters. To make up the gap between theory and practice, liberal arts majors need to participate in research assistantship, internships and well recognized competitions.

Secondly, the job market are in increasing demand of interdisciplinary talents, which puts liberal arts majors at disadvantage. For journalists to cover energy, they need to have at least basic knowledge in energy forms, generation and transformation; for public policy makers to design technology-promoting policies, they have to understand technologies; for lawyers to win patent infringement litigation in the Smartphone War, they have to understand all different things about smartphone as well. Nowadays, there are plenty of pure hard-science jobs but there are not much pure liberal arts jobs. It is easier for a pure hard-science major to gain skills trained in liberal arts education but it is much more difficult for a pure liberal arts major to do so vice versa.

Third, the standard deviation for salary is larger for a liberal arts degree than for an engineering degree, because engineering and statistic students learn hard skills that meet hard demand, for example how to master a software. Thus engineering and statistics students depend less on the reputation of their college, while liberal arts students rely more on signal effects of their college. Since PayScale constructs its report on 10,000 colleges and universities, the employment situation would be better for liberal art fresh graduates from top universities, for example University of Michigan.

In respond to the reasons are suggestions for current liberal arts majors to maximize the benefit from a liberal arts degree. First, try to build on soft skills such as critical thinking, team work, leadership and so forth through internships and extracurricular activities. Second, have a second major, or minor, or even some courses on mathematics, statistics and hard-science. Third, get into a good college or university because signal matters sometimes. Finally, despite our focus on employment in this article we want to make it clear that university education is not just about employment. A liberal arts degree helps student understand history and culture which will benefit students in the long-run and the benefit cannot be captured by employment data or salary numbers. After all, university students need to find out their own interests and passions, working hard not just to look for a job, but to find a career.